Our Way Forward

Indigenous People's Education During COVID-19: An Environmentalist's Perspective

Like many people, I am fearful of the pandemic—especially for the Indigenous Peoples (IPs) with whom I work. I have long valued the IPs’ intimate relationship with the natural environment and expertise on the identification and ecology of plants and animals.

Like many people, I am fearful of the pandemic—especially for the Indigenous Peoples (IPs) with whom I work. I have long valued the IPs’ intimate relationship with the natural environment and expertise on the identification and ecology of plants and animals. With this global pandemic, I now fear for these communities, particularly for the elders who bear the culture and who are most at risk. If these culture bearers and leaders get sick and die, the loss would be devastating not only for their families and close-knit communities, but for their entire ethnolinguistic group and far beyond. Indigenous peoples are identified as belonging to 110 ethnolinguistic groups and are estimated to comprise 12-17% of the total population of the Philippines1, any losses of their culture diminish the richness of our Philippine heritage.

My fears are grounded in my experience working on Philippine wildlife and especially bats for many years. Like the indigenous peoples whose culture is intertwined with their ancestral domain, I feel a deep connection to nature, and I fear that bats and other wildlife will be persecuted because of concerns of disease transmission. This isn’t a solution to the problem of diseases from wild animals but would threaten the services they provide and the rich heritage of the Philippines.2

Going into the sixth month of the COVID-19 pandemic, I feel hopeful despite my fears. Fear is often an instinctive and immediate response to perceived danger, while hope develops more slowly and is fostered by reflection—which we have had a lot of time to do under community quarantine or lockdown, while still keeping in touch, informed and connected digital technology.

I hope that the disruption due to COVID-19 (especially in traditional classroom teaching) becomes an opportunity for working together to try new educational approaches. However, these new ways of learning need to be sensitive to the context of IP education.

Ethnoecology: Intimate Indigenous Environmental Knowledge

When discussing IP Education, it is good for us to consider what it means to be “educated.” Often I hear an IP person referring to himself or others as “walang pinag-aralan” or “walang grado.” But as the educator and environmentalist David Orr said almost 30 years ago, “… [T]he only people who have lived sustainably on the earth without damaging it could not read. This does not mean they were ignorant. To the contrary, they had enormous amounts of knowledge. Indigenous peoples’ knowledge of their ecosystems is extensive. We will never be able to match it.”3

I experienced this first-hand when I conducted my PhD dissertation research on Mt. Kitanglad in Bukidnon, Mindanao. I compared the role of fruit-eating bats and birds in bringing seeds of forest trees into open areas by eating their fruits and defecating or spitting out the seeds, and needed to identify the trees. A forestry professor at a local university was not familiar with mountain vegetation. Fortunately, locals told me to consult Zuilo Oresma, an elder of the Higaonon indigenous ethnic group.

As a boy, Nong Zuilo had accompanied his father in the forest harvesting honey and other forest products—for him, his elders were his teachers and their ancestral domain was his classroom. Nong Zuilo named over 400 different trees and other plants in my forest plots, adding information on when they flowered or fruited and which birds ate their fruits, and showing off by calling out the names of the trees while looking only at their trunks and not their crowns. I had the tree identifications confirmed by checking samples of leaves; Nong Zuilo rarely made mistakes.

The term “ethnoecology” refers to the understanding and knowledge of a local—often indigenous—culture of their natural environment. The word was coined by renowned anthropologist Harold Conklin based on his research on the Hanunóo Manyan in Mindoro. Conklin’s doctoral dissertation in the 1950’s documented their extensive knowledge of plants: they could name and identify more than 1,600 different plant types, with 90 percent being used for food, medicine, or in rituals.4 The Hanunóo Mangyan in Mindoro impressed Conklin with “their literacy so pervasive despite the lack of any formal instruction.” He recounted how Maling, an adolescent Hanunóo girl, learned how to read and write the indigenous 48-character script used for ambahan love poems within six months, by asking help from her older sister and other community members.5

Incorporation of IP Knowledge, Culture and Language into School-based Education

Perhaps due to a colonial mentality, the life, languages, and knowledge of indigenous peoples have scarcely been taught in schools: whether in IP communities or elsewhere. This glaring omission has implications on the cultural heritage of the Philippines in its entirety.

Language is intrinsic to learning content. Over ten years ago, with the aim of helping basic education in rural schools by refining their teaching materials relevant to their own forest and farm environment, I found environment-relevant content could be included in the subjects Makabayan/Aralin Panlipunan (Social Studies), Science, English and Filipino. I abandoned the effort because all instructional materials had to be in what were then the official languages of instruction—English and Filipino—while the languages that the children and their parents knew were their indigenous language and Bisaya. A child taught to read in an unfamiliar language may have the ability to decode the text into sounds and words, but will not grasp their full meaning.

Perhaps due to a colonial mentality, the life, languages, and knowledge of indigenous peoples have scarcely been taught in schools: whether in IP communities or elsewhere. This glaring omission has implications on the cultural heritage of the Philippines in its entirety.

Language is intrinsic to learning content. Over ten years ago, with the aim of helping basic education in rural schools by refining their teaching materials relevant to their own forest and farm environment, I found environment-relevant content could be included in the subjects Makabayan/Aralin Panlipunan (Social Studies), Science, English and Filipino. I abandoned the effort because all instructional materials had to be in what were then the official languages of instruction—English and Filipino—while the languages that the children and their parents knew were their indigenous language and Bisaya. A child taught to read in an unfamiliar language may have the ability to decode the text into sounds and words, but will not grasp their full meaning.

Mangyan teachers on Mindoro with their reviewing workshop outputs, including a map showing the different languages spoken in the community (photo by E.M. Maboloc).

Fortunately, recent policy developments in Philippine basic education affirm IP cultures and the diversity of Philippine languages. The IP Education Program was created in 2011, and emphasizes the importance of partnerships between the school and the community in incorporating indigenous learning systems, knowledge, skills, and practices into the curriculum.6

Mother Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE), which was institutionalized by DepEd in 2009, recognizes that young children learn best in the language used at home, and can better learn other languages, such as English and Filipino, if they have already gained the skills of speaking, reading and writing in their mother tongue.7 The MTB-MLE program is now implemented in 19 widely spoken languages8 out of about 175 languages spoken in the Philippines, of which over 100 are IP languages9. Languages are much more than means of transmitting information, they are intrinsic to cultural identity. The survival of indigenous languages has far-reaching effects, including on global health.10

The DepEd IP Focal Person for Davao City, Ms. Alma Tac-on, recounted an experience when she started going to school. A member of the Bagobo Klata ethnic group, she was teased by her classmates because she misused or didn’t understand words in the lingua franca in Davao, Bisaya. To protect her children from being bullied, their mother decided it would be better if they spoke Bisaya at home. As a result, only the first three of her eight children, including Ms. Tac-on, can speak Bagobo Klata. Now a DepEd supervisor overseeing the IP Education Program in Davao City and the principals of schools in her assigned district, Ms. Tac-on has a strong command of English, Filipino, and Bisaya. But when she speaks with other members of her ethnic group, and especially when she consults the elders, she does so in Bagobo Klata, which gives her access to their indigenous knowledge and culture.

Members of the Matigsalug community in Sitio Gilun, Brgy. Marilog, Davao City, with buckets, dippers and soap provided by Ingle Trust Foundation of Davao to help with hand washing as protection from COVID-19. Nina Ingle is in the front row second from left, next to DepEd IP Focal Person Ms. Alma Tac-on (photo by E.M. Maboloc).

Our small environmental organization has been involved in education efforts with the IP communities of Mindanao, particularly in helping to develop education materials. We have been assisting with workshops of the DepEd Davao City Division IP Education Program in developing literacy materials (Spelling Guides or Orthographies and Primers) in six indigenous languages in Davao City11 with SIL Philippines, which has developed dictionaries, grammars, and other language resources for many IP languages.12 We also gained a deeper appreciation for Philippine languages from linguists from UP Diliman, especially how in Philippine languages the meaning of a word can change with prefixes, infixes and suffixes so that subtle differences can be expressed. And we have been inspired by visiting private IP schools, including Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center13 in Bukidnon and Tugdaan Mangyan Learning and Development Center in Mindoro, and a school run by the NGO SILDAP in Davao Region. We also benefited by regular discussions of an informal group of those involved in IP education in Davao City.

One challenge for both DepEd and private IP schools is the shortage of licensed IP teachers; the costs of formal education especially at college level are unaffordable for many IP parents. The National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP), other government agencies, and some schools and organizations give scholarships, but these still reach only a fraction of IP students. A notable effort is that of the Pamulaan Center for Indigenous People’s Education in the University of Southeastern Philippines in Davao City, which has a residential program for IP student scholars from all over the Philippines. The DepEd IP Education Program gives an annual orientation of school teachers and school heads assigned in schools with IP learners, even if teachers are not IP teachers. They prioritize IP teachers because they can speak in the mother tongue and are role models and inspirations for their IP students.

IP Education during the COVID-19 Times

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, public school teachers will not conduct face-to-face classes until a vaccine has been developed. DepEd has delayed the opening of classes for the 2020–2021 school year to August 24, 2020.14 Students throughout the country will be learning online. In IP areas, even cellphone and broadcast signals can be absent and few children have access to electronic gadgets or even radios and televisions.

The Indigenous People’s Education Office (IPsEO) and IP Education Focal Persons throughout the country have been considering ways not only to address the challenge of how learning materials can be accessed, but how children can be guided in using these materials. As with elsewhere in the country, parents and other family members will have a major role in assisting young children. However, for IP communities the level of literacy and formal schooling in adults tends to be low, making this role more challenging.

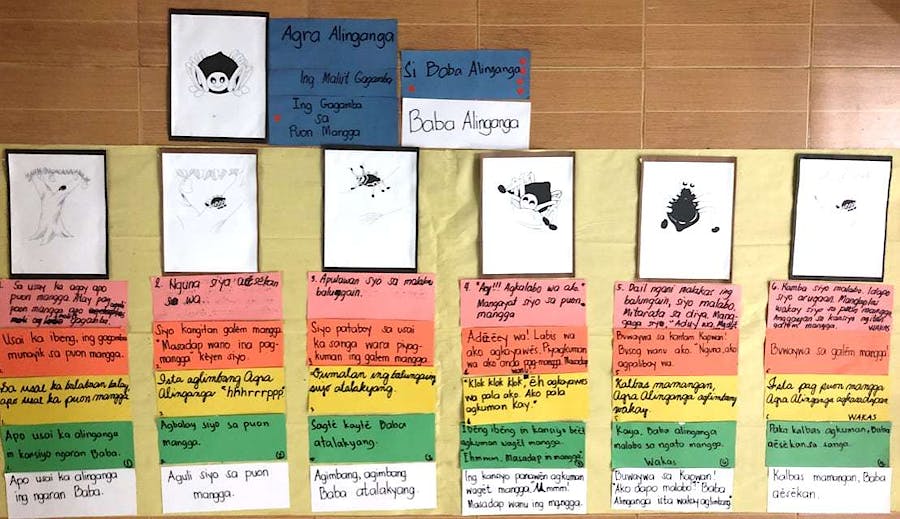

Perhaps, family members can become content sources of the learning materials. They can help make simple stories for children given their knowledge of the language. This became clear to us when we did a workshop with IP teachers in Mindoro, where we asked them to write the text to accompany prepared illustrations for a short book on a spider. They collaboratively created the story of “Baba Alinganga” (Baba the Spider). There was so much emotion and enthusiasm as they delivered their story—a celebration of a language one knows fully well!

Literature in Indigenous Communities

Rizal never became a professor in his life. However, while in exile in Dapitan, Rizal had a boarding high school for boys. Earlier, he documented and illustrated the folktale of the monkey and the turtle. Rizal’s illustrated Monkey and the Turtle was the first Filipino folktale published in Trubner’s Oriental Record in London in July 1889,15 in commemoration of which the National Children’s Book Day was set to fall on the 3rd Tuesday of July. A related annual event is the National Library and Information Services Month, celebrated every November. However, even in IP schools that have libraries, most books are not relevant to the lives of IPs, and not in IP languages.

Teacher participants in a 2-day workshop on Mindoro on making simple books in local languages using SIL’s free Bloom software, with Ingle Trust workshop facilitators Eva Marie Maboloc (far left) and Nina Ingle (second from right).

But how do we produce children’s books in indigenous languages for use in the classroom, reading at home, or local school libraries? A software program called Bloom that was developed by SIL International to help minority ethnolinguistic groups publish books for children can be downloaded for free.16 Bloom makes it easy for authors to create simple books for children, which can be printed on regular paper and folded into slim books. Text can be saved in different languages. Bloom can even make “talking books” so children can hear the text spoken. DepEd with SIL Philippines has been conducting workshops to train teachers throughout the country in using the software. Books and illustrations can be uploaded so that others can use them. We used Bloom in teaching IP teachers in Mindoro and in Davao Oriental how to make simple books; they were able to produce books by the second day of the training.

Drafts of Baba Alinganga (Baba the Spider) in Alangan Mangyan (photo by N. R. Ingle).

With the pandemic, we saw the need for educational materials on COVID-19 for indigenous ethnic groups. IP teachers in the DepEd IP Education Program of Davao City, with help from elders, produced the translations for their six distinct languages. We’ve been gratified by feedback—one local leader reported that children read the posters to their elders, who said they could understand the information because it was in their language. With support from SIL International, which is supporting efforts in various countries to produce COVID-19 information in local languages,17 we will be working on posters in other indigenous Philippines languages.

Action for the Future – Learning about and Advocating for IP Groups in the Philippines

How can we learn about, celebrate, and advocate for IP groups in the Philippines even during the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic? Here are some suggestions:

1. Learning more about and celebrating IP groups and their languages. A very readable and moving example is Stuart Schegel’s Wisdom From A Rainforest: The Spiritual Journey of an Anthropologist. It is an account of his two years with the Teduray in Mindanao, available from the Ateneo de Manila University Press. Another good starting point from the perspective of languages would be the annual Communities of Practice conferences, organized by SIL Philippines and partners. Here, practitioners supporting IP community development from diverse sectors gather to share their experiences in supporting IP communities, their successes and challenges and opportunities for collaboration among themselves.18

2. For educators, incorporating information on IP life, cultures and knowledge into subjects they teach. Examples are the inclusion of indigenous folktales into language subjects, knowledge about plants and animals or forests and agriculture into science. Undergraduate student thesis projects could include research on indigenous language and culture–an opportunity to really contribute new information.

3. Helping to make educational materials for rural children. Most available children’s books are written by foreign authors or by those from an urban environment. Those people who are familiar with the rural or upland context and who have time on their hands—perhaps prison inmates, students (perhaps given this task as an assignment), or retired professionals—can help make simple books. Creating simple illustrated books in Bloom and then uploading them into the Bloom library19 makes them accessible for translation into other languages including IP languages.

4. Supporting scholarships for IP students help them have the standing in society to contribute to their communities in various ways, including education.

5. Supporting local initiatives emerging from IP communities to address their basic needs for food, health services, and education, while respecting their identity, aspirations, and rights.20 These rights include the integrity of IP ancestral lands, which in the COVID-19 pandemic have been identified by the Department of Agriculture as “idle” lands for commercial food production,21 risking the fragile upland natural environment that supports Philippine biodiversity and regulates water cycles upon which downstream communities depend.