Our Way Forward

Political Empowerment as Protection: The Way Forward for Filipino Domestic Workers in the Time of COVID-19

Social media has recently been bursting with positive messages about “enjoying being stuck at home” during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Social media has recently been bursting with positive messages about “enjoying being stuck at home” during the COVID-19 lockdown. Indeed, this pandemic has forced families to stay at home not just for the safety of its members but for the community as a whole. We see on social media various images of parents and children cooking, gardening, and baking together or Marie Kondo-ing their clothes, cleaning the house, or doing a complete home makeover.

Those positive images, however, do not present the complete picture. In so many instances, we do not see “the people behind the scenes” that we have largely depended on before the pandemic: the domestic workers.

As per the ILO Domestic Workers Convention of 2011 and RA 10361 or the Kasambahay Law passed in 2013, domestic work is defined as “work performed in or for a household or households” and domestic worker or “kasambahay” refers to “any person engaged in domestic work within an employment relationship such as, but not limited to, the following: general househelp, nursemaid or “yaya”, cook, gardener or laundry person but shall exclude any person who performs domestic work only occasionally or sporadically and not on an occupational basis.”

When the pandemic hit the global community this year, it drastically affected the labor market, including the fate of millions of domestic workers both here and abroad. According to the 5th edition of the ILO Monitor released last June, an estimated 55 million or 72.3% of domestic workers around the globe found themselves at great risk of losing their main source of livelihood due to drastic measures being taken by various governments, such as nation-wide lockdowns, the suspension of classes and regular work, the imposition of travel bans, and the shutting down of international borders.

It was also reported that more than two-thirds of those who are at-risk are women. In Asia and the Pacific region alone, women make up 58.2% of domestic workers. Many of them are also migrant workers, who had to leave their homes and families behind in order to seek for better job opportunities in a foreign, distant land. Coupled with the lack of access to social protection, the threat of gender and racial discrimination, and the stress and anxiety brought about by homesickness and an uncertain future -- it is no surprise that domestic workers have become one of the most vulnerable sectors during these trying times.

According to the latest briefer of the Department of Labor and Employment released in 2011, there are around 1.9 million domestic workers in the country, mostly women (more than 80%) and mostly young (32% are in the 15-24 age bracket). Of these, around 30% or 585,000 are in live-in arrangements. Meanwhile, the Preliminary Results of the 2019 Annual Estimates of Labor Force Survey (LFS) conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority report that 4.3% (around 1,823,200) of the total 42.4 million employed in the previous year is composed of workers in private households.

Meanwhile, Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) statistics last year show that of the 2.3 million OFWs, roughly 37.1% or 850,000 belong to “elementary occupations” foremost of which pertain to the subgroup of “cleaners and helpers.” Almost 60% of those in engaged in elementary occupations are women. The top 5 destination countries of these domestic workers are Hong Kong, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

However, despite the many stories that herald them as modern-day heroes, we have to remember that even without a pandemic, the world of work for these domestic workers has always been far from ideal. To interrogate how COVID-19 has impacted on the less-than-perfect lives of these domestic workers, the Working Group on Migration of the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University (WGM) organized an online interview with PH-based Maia Montenegro and Alladin Diega, Hong Kong-based Shiella Estrada, and Kuwait-based Mary Ann Abunda.

Maia Montenegro is the Deputy Secretary General of the United Domestic Workers of the Philippines (UNITED). Together with Labor Education and Research Network (LEARN) organizer, Alladin Diega, the group inquired about the situation of domestic workers in the country.

According to Alladin, 40% of their members are employed under live-in arrangements, which means that oftentimes, work hours are not strictly defined and followed, given that they stay with their employers 24/7. Majority are considered as “live-outs,” where the worker would regularly go to the employer’s house from Monday to Friday, sometimes even on weekends, and do household chores within a specified period of time.

Due to lockdowns and community quarantine rules being implemented by the government, many of those who fall under the “live-out” arrangement are not able to go to work. “Right now, parang malaking oras namin, wala kaming choice kung hindi intindihin ‘yung praktikal na problema ng mga domestic workers, like ‘yung marami sa kanila ay wala talagang access sa pagkain. As basic as that… Dito halimbawa, tayo sa Quezon City, may mga areas ‘yung mga local domestic workers, ‘yung mga areas nila hindi talaga napapaabutan hanggang sa ngayon ng food packs,” Alladin shares.

Those living with employers also face a lot of challenges. For instance, in big households where two to three kasambahays are employed, tasks and responsibilities would usually be split and shared equally among them. But because of the uncertainty brought about by the pandemic, many live-ins have decided to return to their home provinces. This has resulted to heavier workload and longer working hours for those who were left behind.

To know more about the situation of Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong and Macau, the group interviewed Shiella Estrada, Chairperson of the Progressive Labour Union of Domestic Workers – Hong Kong (PLUDW-HK).

Similar to those based in the Philippines, one of the biggest challenges faced by Filipino domestic workers is the heavy workload at home. Since most employers would stay and work from home, there is added pressure on the part of the domestic worker to perform well and serve more people. And since employers are oftentimes present within close range, many domestic workers would skip taking breaks and rest periods – lest they be accused of being lazy and underperforming. “‘Pag nag-stay-in ang mga employer, mas maraming trabaho. Walang tigil na trabaho. Kaya kung ‘yung dati, nagtatrabaho sila ng 16 hours per day, ngayon nagiging 18 ‘yan. Tapos dati nakakaupo pa sila kahit papaano. Ngayon hindi na, kasi parang ang katuwiran nila, parang may CCTV sa loob na nung bahay kahit wala,” Shiella narrates.

Moreover, while most work-related tasks that require going out like bringing their alagas to their tutors or fetching them from school, have become less frequent, a big chunk of the burden has now shifted to the confines of the home. Aside from preparing meals for a larger group, they are also required to do more cleaning and housekeeping, increasing their exposure to harmful chemicals and substances that pose a threat to their health. According to Shiella, “Kung noon twice lang kami nagpe-prepare ng meals, ngayon three times na. Minsan, five times pa kasi may mga snacks pa sila, may mga tea time pa sila. Kaya talagang nag-doble-doble na ‘yung job sa loob ng bahay.”

Filipinos in Macau also suffer the same fate. Those who work in hotels and casinos lost their jobs, resulting to the non-renewal of their working visas. Sadly, this has given birth to more problems and concerns on the part of our workers. Since going back home is not an option for many of them, they would usually ask help from fellow kababayans who in turn, will share meals and offer their small living space as a temporary shelter.

This situation is heartbreaking because many of these overseas domestic workers are now unable to send money to their loved one back home. Worse, families of OFWs were said to have been excluded by some barangay officials from receiving government aid and support during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, those who decided to fly back home are faced with the same dire situation. While the Duterte administration struggles to provide a clear plan in providing livelihood opportunities to our overseas workers, many of them remain stranded for months in the capital and are still waiting to go back to their provinces.

Last to share the stories of Filipino overseas domestic workers is Mary Ann Abunda, Founding Chairperson of the Sandigan Kuwait Domestic Workers Association (SKDWA).

Similar to those based in Hong Kong and Macau, Filipinos in Kuwait are struggling to adjust to the new nature of domestic work as a result of the pandemic. According to Ann, working hours have become more irregular and are oftentimes extended than the usual. Many workers are left with no choice but to skip taking breaks and heed the demands of their employers 24/7. “Sa panahon kasi ngayon, kailangan mong mahalin ang trabaho mo,” she says. In fact, many of them would rather stay and take on difficult jobs abroad than end up being unemployed in the Philippines.

Despite the many hardships Filipino domestic workers have to go through every day, the pandemic has also created a stronger bond and mutual understanding between employer and worker. Ann shares that instances of maltreatment and domestic abuse have lessened and both parties are able to be more understanding and treat each other kindly. This is especially true during the Ramadan season when employers who are fasting would usually tend to be easily irritable and impatient. Because COVID-19 has resulted to the closing of borders, hampering the influx of foreign domestic workers and the deployment of additional workforce, employers and domestic workers have learned to foster dialogue and openness within the confines of the home, lest the former end up having no one to depend on and the latter losing his source of income.

The pandemic has also deepened relationships between the migrant worker and his family back home. Narrating how family members would now call and regularly check up on the migrant worker, Abunda comments, “Parang nagkaroon ng mas communication ngayon.” According to her, this is in stark contrast to pre-COVID days when family members would only call if they need money to be sent to pay monthly bills and expenses.

The accounts of Maia, Shiella and MaryAnn about the impact of COVID-19 on domestic workers are essentially narratives of marginalization – economically, political and socially. These workers, like everyone else, are stuck at home – but not in the safety and comfort of their homes. Especially for domestic workers abroad, COVID-19 is a time of being away from family when family members need to be together the most.

For the WGM, these narratives speak for themselves and readers are invited to reflect on the value – and the neglect – of domestic workers during this pandemic. More importantly, we invite readers to reflect on what’s ahead for domestic work and domestic workers post-COVID 19.

On the part of the WGM, these are our reflections.

1. Domestic work must be recognized as frontline, essential service and domestic workers as frontliners.

Domestic workers don’t work from home, they work for homes. This is true especially for those under live-in arrangements. At a time of a health pandemic, that means working for homes that could have family members sick with COVID-19. Like many healthcare workers, these domestic workers provide care to households trying to stay healthy and survive this pandemic. Their great value to society during these extraordinary times, thus, must be acknowledged and evaluated accordingly. Especially at a time of crisis, these domestic workers must not be made invisible.

To raise the visibility of domestic workers, governments here and in destination countries, must keep tabs on the health, whereabouts and living and working conditions of domestic workers.

For Shiella, our government, through the Consulate in Hong Kong, should find ways to immediately respond to the basic needs of migrant workers during this pandemic. This includes the provision of face masks and temporary shelters for distressed and terminated workers.

For Ann, this means that both governments must work together in looking after the mental well-being of domestic workers in Kuwait. Given the rising number of suicide cases among migrants, relevant information about COVID-19 and adequate support in the form of free counseling must be provided to address the tendency of workers to wallow in hopelessness, self-pity, and despair. Providing psychosocial support can help migrant workers maintain a positive outlook while battling the everyday demands at work.

2. Domestic work must be treated as work and professionalized.

Across the three narratives that pertain to work in several Asian and Middle Eastern countries, there is a common thread: being “stuck at home” in a time of pandemic means “more,” not less work. Domestic workers are now at the beck and call of employers who stay and work from home. Because of this, work hours have ceased to be limited and rest days are now a thing of the past. Wages remain the same, however, as additional work is not compensated.

Domestic work needs to be monitored more during this time of pandemic. While it is understandable for employers to keep their domestic workers at home as a means to comply with government containment measures, these employers must also be cognizant of the limits that domestic workers must keep – by virtue of their being workers. Work hours must be limited and additional work must be negotiated and compensated.

If domestic work is to be considered work, domestic workers should be accorded all labor rights including the right to organize into trade unions or workers’ associations. As the narratives show, domestic workers are best protected when they are aware of their rights and are empowered to exercise these rights.

Moreover, the PH government must work closely together with the destination country to ensure that proper rules and guidelines on wage increase and adjustments are set in place and implemented. Proper legal assistance and protection must be made available to the aggrieved party, and that adequate punishment be given to violators. The demand for social inclusion and accountability must be placed at the front and center of policy-making and bilateral agreements.

3. Migration of domestic workers must be lessened, despite the likely continued demand for domestic workers abroad.

All three informants are agreed that while many employers of domestic workers are also likely to face job loss or wage reduction because of COVID-19, there will always be a growing demand for domestic workers.

If there is one thing that this pandemic has taught us, it is that there is still a lot of work to be done. Therefore, we must roll up our sleeves and raise awareness on the different issues that affect many of our domestic workers both here and abroad.

Moving forward, Shiella also stressed the importance of empowering our domestic workers by letting their voices be heard, and by working closely with government in introducing reforms and creating new policies that will address their needs. In the end, she laments: “Hindi ko alam kung ang gobyerno natin ay handa kasi parang sa lahat ng narininig namin dito’t nababasa, parang ang dami-dami na nilang pinapauwi pero hindi ready ‘yung gobyerno natin para bigyan ng protection o bigyan ng kabuhayan ‘yung mga umuuwi.”

Ultimately, the accounts of Maia, Alladin, Shiella, and Mary Ann, should remind us that domestic work is difficult work. It is, in fact, essential work, especially during these difficult times. And since it contributes to the care of citizens and the well-being of society, we must raise its status and work together in ensuring that our domestic workers will receive the support, protection, and recognition that they deserve.

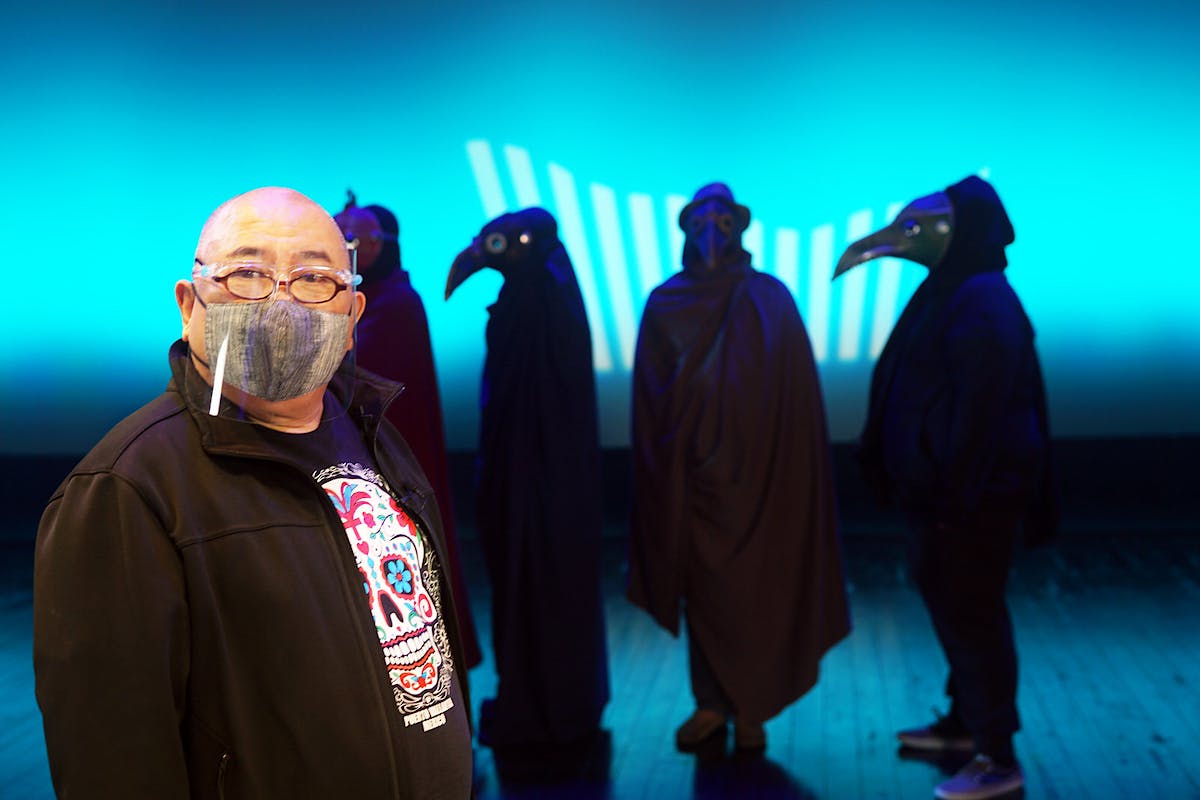

We now invite everyone to watch the video above and listen to parts of the interview.

Carmel (Melay) Abao is an assistant professor of the Ateneo de Manila University Department of Political Science. She teaches Philippine politics and government, classical political theory and international political economy.

Maria Elissa Jayme-Lao is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University. She is also a Research Associate at the Institute of Philippine Culture. Her current research includes work on Philippine foreign policy, migration and Philippine elections, democratization in the Philippines and Disaster Management.

Oliver John C. Quintana is Director of the Korean Studies Program and Instructor at the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University. He has taught several undergraduate courses including Philippine Politics and Governance, International Relations, Comparative Politics in Asia, and Korea-ASEAN Relations. His research interests include Southeast Asian politics and society, international relations, migration, nationalism and modern Korean history.